Interview with Christopher Schroeder

How often do you travel to Iran?

I have gone on two trips to Iran, in spring of 2014 and 2015. They were coordinated by a small group of members of the Young Presidents’ Organization and World Presidents’ Organization — a global network of some 22,000 CEOs. This subgroup, called the Presidents’ Action Network, has done previous trips to conflict areas such as Israel and the Palestinian Territories, India and Pakistan, North Korea and others. The group has organized three trips to Iran in the past three years, and I have attended the last two. About a dozen CEOs from the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada, with a few spouses, went on the 2014 trip. This year, the group was a bit larger — about 24 travelers in all.

I have gone on two trips to Iran, in spring of 2014 and 2015. They were coordinated by a small group of members of the Young Presidents’ Organization and World Presidents’ Organization — a global network of some 22,000 CEOs. This subgroup, called the Presidents’ Action Network, has done previous trips to conflict areas such as Israel and the Palestinian Territories, India and Pakistan, North Korea and others. The group has organized three trips to Iran in the past three years, and I have attended the last two. About a dozen CEOs from the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada, with a few spouses, went on the 2014 trip. This year, the group was a bit larger — about 24 travelers in all.What is the purpose of these tours? What did you observe?

In light of Rouhani's election in 2013, and the broader discussions between Iran and the United States this past year, we felt that this was a perfect time to explore in-person and on the ground what the business and economic climate in Iran is. Little of what we saw is what we are normally exposed to through American news, which tends to focus on areas of political conflict and the nuclear talks. The frame of reference for many Americans is still based on the takeover of our embassy in Tehran, the Islamic revolution and subsequent decades of tense relations — especially during the Ahmadinejad years (2005-2013).

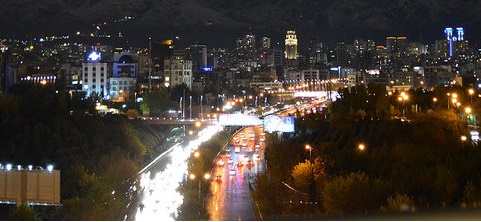

Few of us had a sense for what Tehran looked like — the quality of roads, the quantity of traffic but of newer cars, how most signs are also in English, how couples and families in parks show open displays of affection. We were deeply impressed by the quality of the infrastructure, the talent, and educational skill (especially engineering) of the youth. We were treated with great warmth and respect as Americans in both meetings and random encounters. There was strong pro-deal sentiment — even presumption of a nuclear deal — among virtually everyone we met.

Few of us had a sense for what Tehran looked like — the quality of roads, the quantity of traffic but of newer cars, how most signs are also in English, how couples and families in parks show open displays of affection. We were deeply impressed by the quality of the infrastructure, the talent, and educational skill (especially engineering) of the youth. We were treated with great warmth and respect as Americans in both meetings and random encounters. There was strong pro-deal sentiment — even presumption of a nuclear deal — among virtually everyone we met.Iran is a surprisingly wired country. Nearly 65 percent of homes have broadband access. Mobile penetration is more than 120 percent, meaning people have more than one phone or SIM card. Iranians are now using 40 million smartphones (full mobile computing devices) from brands including Samsung, HTC, a local carrier (all using Android software) and, despite the sanctions, Apple. I was told that there are more than 6 million iPhones in the country, mostly attained through Istanbul and Dubai.

Last year there was very limited access to 3G data on mobile phones, perhaps as low as one million subscribers. We were told mobile carriers in Iran were going to roll this out aggressively in the following year, but we had strong doubts. One year later, however, there are 20 million 3G and now 4G subscribers.

Last year there was very limited access to 3G data on mobile phones, perhaps as low as one million subscribers. We were told mobile carriers in Iran were going to roll this out aggressively in the following year, but we had strong doubts. One year later, however, there are 20 million 3G and now 4G subscribers.Everyone across age categories accesses unfiltered internet through virtual private networks (VPNs). Not only are Facebook and Twitter ubiquitous, but, for the first time, Iranian officials noted to our group that the two social media platforms would be useful market distribution channels for Iranian businesses wanting to reach consumers. Both sites however, are technically banned.

The government runs 32 tech “incubators” around the country, focused on key strategic areas such as agriculture, banking, security, education and infrastructure. There is also a nascent but rapidly growing private startup community, often hosted at universities, where entrepreneurs are creating their own version of successful companies in the West as well as services for the Iranian and regional markets. For example, the eCommerce company Digikala doubled in value since last year to a reported $300 million, and there were Iranian versions of audio books, eBay, travel booking sites and more. Government planners hope that the eHealth space will be worth more than $1 billion in 2017, and that their efforts to lead in mobile payments will “eliminate the need for plastic” (mostly debit cards) in several years.

We were told repeatedly that Stuxnet — the computer worm that allegedly targeted Iran’s nuclear program — was a wakeup call for people to start taking technology more seriously. The government invested over $4 billion in high tech infrastructure last year, and has plans for another $25 billion in the next three years.

International sanctions on hard goods seemed less concerning to everyone that we met, as almost anything was attainable at a price. Sanctions on banking and the SWIFT global financial service, however, drove the economy to its knees in recent years. Iranians talked about reducing inflation from 50 percent to 14 percent in the last year in large part due to significant currency devaluations — but there was some doubt about that, and the cost has been great. While we saw few signs of abject poverty in Tehran, many people have had to take more than one job in the last year.

Our hotel was packed with Europeans — mainly Germans and Scandinavians — both business types and middle aged tourists. The great stand outs, however, were the Chinese travelers. Even the young people at startups we met said they had seen them. Chinese smartphone producer Xiomi is reportedly making moves to come to Iran’s mobile markets aggressively. Several Iranians told us that 25,000 to 30,000 or more Chinese expatriates are now in Iran, many of whom speak Farsi. But we could not confirm this.

Our overall sense is that Iran is one of the most advanced emerging markets we have seen waiting to re-enter the global community. Corruption is quietly mentioned as massive; the fact that people have long worked around systems has bred a strange ethic into the business culture. But the talent, tenacity, and global mindedness were concrete and universal.

Tehran's high-tech award-winning bridge designed by a 26-year-old Iranian woman: http://t.co/wGVlqhOwth pic.twitter.com/HsGLM0j6ec

— Saeed Kamali Dehghan (@SaeedKD) April 20, 2015The greatest take-away from the trip is that the new generation — people under age 35 who represent 60 percent of the country's population — came of age well after the Islamic Revolution. Many were engaged in the 2009 Green Movement protests. Most are utterly wired, and see the world around them daily. Their premises on how they see the world and ambitions are different than their parents. On the current path, the youth do not see themselves attaining their dreams, or even moving out to live in their own apartments. They see increased global engagement as the single greatest hope for self-actualization and economic success.

What are the prospects for American investment in Iran?

The prospects are significant. Many American brands have long been popular and accessible there, other, newer brands — often tech enabled like social networks, apps and music — have high demand and are accessible on Iranian mobile devices. From machine tools to software, there is significant opportunity. The travel business will also be significant — as there were very few four or five star hotels in and around some magnificent tourist areas.

Who have American CEOs met with in Iran?

We travelled to Iran as tourists, and visited the remarkable historic and cultural centers near Shiraz, Isfahan and Tehran. But we had a strong focus on understanding the business and political landscape. So we met leading figures in banking, private equity, venture capital as well as some of the very influential heads of conglomerates across diverse industries. We met with members of the art community, and one (albeit reformist) grand ayatollah in Qom. The next generation tech startup communities and recent university grads were particularly interesting to me.

We travelled to Iran as tourists, and visited the remarkable historic and cultural centers near Shiraz, Isfahan and Tehran. But we had a strong focus on understanding the business and political landscape. So we met leading figures in banking, private equity, venture capital as well as some of the very influential heads of conglomerates across diverse industries. We met with members of the art community, and one (albeit reformist) grand ayatollah in Qom. The next generation tech startup communities and recent university grads were particularly interesting to me.There is no question that the majority of what we saw is what the trip handlers wanted us to see, though we were struck by many surprises even in that lens. We were aware of hardliners that oppose more engagement with the West, but we did not meet with any during our trip.

We were told that only 500 to 1,000 visas are granted per year to American travelers, and mostly for tourism. But clearly more and more Americans are beginning to seek out opportunities should relationships open up. Many people positioned in Dubai, Istanbul and elsewhere are closely monitoring the situation.

What are potential obstacles to American investment?

Right now, beyond the obvious sanctions, they are legion. Rule of law, property rights, and the ability to repatriate capital are among the greatest challenges in emerging markets and are significant in Iran as well. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei does not have an obvious successor, and that lack of clarity introduces risk. Whether or not reaching an agreement on the nuclear issue opens up the possibility for dialogue on other regional issues remains a central question. There is a sense, at the same time, that entry into the global market is essential to Iranians.

What could be the timetable for investment if Iran and the world’s six major powers finalize a nuclear deal by June 30?

The timetable would be heavily dependent on the speed of sanctions relief, especially the first wave and its size. Real success in newer markets requires trusted relationships, the time to cultivate them and a sense of co-authorship in transactions. Access to markets through technology and the quality of Iranian infrastructure may make this all move much faster there than in any other new market of the last two decades. But the challenges are significant.

Christopher M. Schroeder is a U.S.-focused venture investor and author of Startup Rising: The Entrepreneurial Revolution Remaking the Middle East. He was formerly co-founder of healthcentral.com, which was sold in 2012, and CEO and Publisher of Washingtonpost.Newsweek Interactive. He may be followed at @cmschroed.

Photo credits: Modares Expressway by Saeid Zebardast (cropped) via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0), Unofficial Apple store by Robin Wright, Azadi Tower by Maral Noori

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org