Semira Nikou

The voice of Ali Larijani, Iran’s parliament speaker, disrupted our dinner party.

We left our plates filled with fruits and nuts to huddle around the television, as the speaker read the names of President Hassan Rouhani’s cabinet picks one by one, announcing whether or not each had been approved by the parliament. One of the guests, a journalist, let out a sigh of relief with Bijan Namdar Zangeneh’s approval as petroleum minister. Zanganeh, who had served in the same position under former President Mohammad Khatami’s reformist administration from 1997 to 2005, was a key candidate whose nomination had been hotly challenged by Iran’s conservative parliament.

With parliament ultimately approving 15 out of the 18 proposed ministers, the administration of hope—as Rouhani’s presidency is referred to—had delivered a competent cabinet. Now we could eat.

There is a new mood in Iran. I recently visited Tehran in August 2013, four years after my last trip in June 2009. Much has changed since. The Iran of 2009 and the Iran of 2013 are two different places.

Tehran has gotten greener and more developed, the value of Iran’s currency to the dollar has dropped by threefold, and it has become nearly impossible to find good sangak bread anywhere. But the real change is subtler. There is an optimism I sensed when listening to family members—even those who had not voted in the 2013 election because of their disillusionment over the 2009 results—journalists, including one who was now ecstatic that his efforts to get a U.S. work permit had failed months prior and forced him to return to Iran, and an elderly taxi cab driver who dropped me off at home late one evening, refusing to drive away until I had safely entered the house.

As an artist friend who voted for Rouhani described to me, “After the election, people would smile for no reason. I cannot point to anything specific, but something has changed.” He continued to tell me about the night of Rouhani’s election, how he and his friends had poured into the streets in affluent northern Tehran, booze in hand, joined by hundreds of thousands of others. “I was taking vodka shots in front of police officers. They did not say anything.”

The election of a 64-year-old cleric had elicited the level of excitement typically seen only after soccer-match victories. In fact, the celebration continued days later when Iran qualified for the 2014 World Cup by beating South Korea.

On June 20, 2009, I had arrived in Tehran a day after Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s famous Friday sermon, in which he validated the contested election results and essentially sanctioned the use of violence against protestors. I went to a demonstration that afternoon. Thousands of others marched around me but the environment was eerie. Black-clad police officers with batons attacked people who tried to agglomerate, while plain-clothes officers and basij paramilitary forces engaged in their own unchecked violence against protestors. Neda Agha Soltan was shot and killed that evening. The young woman’s death, captured on video, became a symbol of both the opposition Green Movement and of government brutality.

This year, I was in Iran for the Friday sermon itself and, again, there were thousands around me in the streets. It was Eid-al-Fitr, the holiday signaling the end of the holy month of Ramadan. The supreme leader’s Eid-al-Fitr sermon had historically taken place at the massive Mossalah mosque, but has relocated to the smaller, and more controlled, Tehran University campus since the 2009 election to prevent protestors from disrupting the sermon. Despite some predictions, the sermon was once again held at Tehran University this year.

I decided to attend out of curiosity; to see how many Iranians actually participated in this event. Despite living in Iran for six years—and even serving a brief tenure as prayer leader at my elementary school—I was taken aback by the crowds that swarmed the area on that early Friday morning.

“You will feel like it is judgment day,” a journalist aptly told me. The area around the university was so crowded that the taxi had to drop me off a mile away. Buses shuttled people to the prayer area. I started walking in the same direction as hundreds, and soon thousands, of other people. I felt extremely awkward in my bright orange, Hawaiian print scarf among the sea of black, brown, and dark blue chadors and other conservative Islamic wear. I half expected a police officer to target me for my ostentatious clothing. But that did not happen because the atmosphere was celebratory. Families jubilantly walked together as the hum of prayers permeated the area and tens of sadaqeh stalls encouraged visitors to give charity. The crowd got denser and denser. Lacking perseverance, I left before reaching the prayer area.

Two elections, two presidents, and two very different outcomes. I hope that the new mood in Iran will not only facilitate national reconciliation, but also renew efforts for diplomacy. Nuclear negotiations between Iran and the permanent members of the United Nations Security Council plus Germany (P5+1) largely failed in 2009 because a wide range of Iranian political actors refused to rally behind President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s effort at a nuclear deal, viewing it as attempt by the administration to consolidate power.

But today, the mood is different. The country is ready to heal and move past the trauma of the past four years. That is why we watched and discussed the televised parliamentary debates over the new administration’s ministerial nominations and the final results read by Larijani so attentively. We felt that who was chosen actually mattered.

1) Customers waiting in line outside Kia Gallery, a popular and trendy jewelry boutique in northern Tehran. Sanctions don’t seem to have affected this store’s business!

2) Mehr Housing Units in the suburbs of Tehran. Former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad introduced the “Mehr Scheme” for low-income housing. But the program has been criticized for failing to deliver to all those it had promised, its poor quality construction, and contributing to the country’s inflation and budgetary problems.

3)Haft-e Tir (7th of Tir) Square in Tehran. The square gets its name from June 28, 1981, when a bomb explosion at the Iran Islamic Republic Party headquarters killed 73 Islamic Republic officials. At Haft-e Tir, like elsewhere in Tehran, pedestrians can opt to cross the city’s infamously busy streets by using pedestrian bridges—though Iranians tend to brave the crossing by foot.

4) A vendor’s spread at Jomeh Bazaar (“Friday Bazaar”), a popular market that takes place in Tehran on Fridays. Hundreds of vendors fill a multi-floor parking lot selling crafts, textiles, and antique goods from Iran and its neighboring countries. Haggling is a must.

5) A quiet afternoon at Chitgar Lake, an artificial lake in northwestern Tehran. The 120-hectre lake was officially opened in May 2013 and is popular with residents who want to take strolls, ride paddle boats, or enjoy recreational facilities. Despite the lake’s popularity with visitors, critics are concerned over its environmental impact, in light of Tehran’s limited water supply.

6) A show of lights at the Holy Defense Museum in Tehran. The museum and its surrounding areas, which include Taleqani Park, were packed with thousands of people and hundreds of honking cars during Ramadan nights. The city organized lively events every night during the holy month, featuring live music (including gheri—danceable—music), comedy skits, and stories about martyrs and the Iran-Iraq War. The park had built-in BBQ grills and tents, where people grilled kabobs, smoked ghelyoon (hookah), and watched the show on large projectors.

7) Folks exchanging currency at the Tehran Grand Bazaar. The rates change daily based on a variety of factors including reactions to domestic and global events. It is higher than the official rate. Few people, usually only importers and exporters, are qualified to get the official rate.

8) Iftar (evening meal during Ramadan) at a family gathering.

9) Hikers breaking fast at Darakeh, a popular hiking area in Tehran’s Alborz Mountains. During fasting period (daytime) in Ramadan, people are not allowed to eat or drink in public, so restaurants do not open until sundown. This café started serving customers before the day officially ended because it was the last day of Ramadan and, well, it was okay to take it easy.

10) Road to Bargeh Jahan (“bargejoon”)—meaning “leaf of the world” in reference to the way the village looks like a green leaf cradled among mountain slopes. Bargejoon is a village in northeast of Tehran. It becomes nearly deserted during the cold winter months. In summer, villagers return to harvest a variety of agricultural products, including fruits such cherries, apricots, apples, and walnuts, while Tehranis use it as a summer retreat.

11) The Tehran metro, which currently has four operational lines and a fifth line is being built.

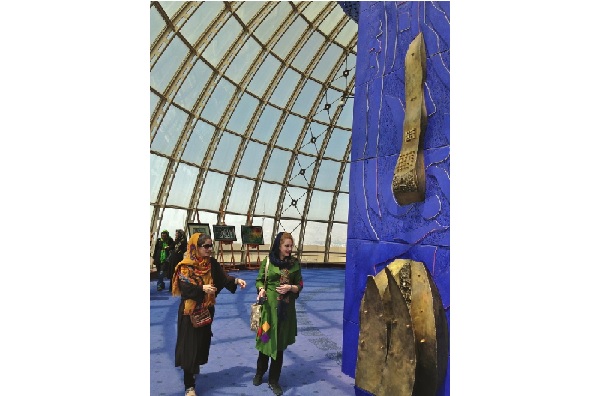

12) View from Borj-e Milad (Milad Tower). At 435 meters, the Milad tower is the tallest tower in Iran and the sixth tallest telecommunications tower in the world. The tower features a panoramic view of Tehran, a shopping area, restaurants, and art exhibits.

13) Visitors at Borj-e Milad (Milad Tower).

14) Tehran’s two-level Sadr Highway. Construction on the second level was to be finished earlier this year, with the city using a countdown to widely advertise its completion. But the project remains unfinished. Part of the difficulty in completing the second level is that it requires closing sections of the busy Sadr Highway—which is why knowing detours and shortcuts in Tehran is a highly valued skill.

15) Visitors at Emamzadeh Hashem Shrine outside Tehran.

This article was originally posted on Muftah.org.

Semira Nikou is a research associate at the Public International Law and Policy Group (PILPG) and is pursuing a degree at American University Washington College of Law. She previously was a contributing author to The Iran Primer.